Japan has an old proverb: “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down.”

While in China, there is a saying, “The higher the tree, the stronger the wind.”

In a critical lens, both idioms illustrate harmony and unity – a vital essence of Asian culture and heritage. Nevertheless, the proverbs also shed light on a contrasting school of thought: conformity and crab mentality.

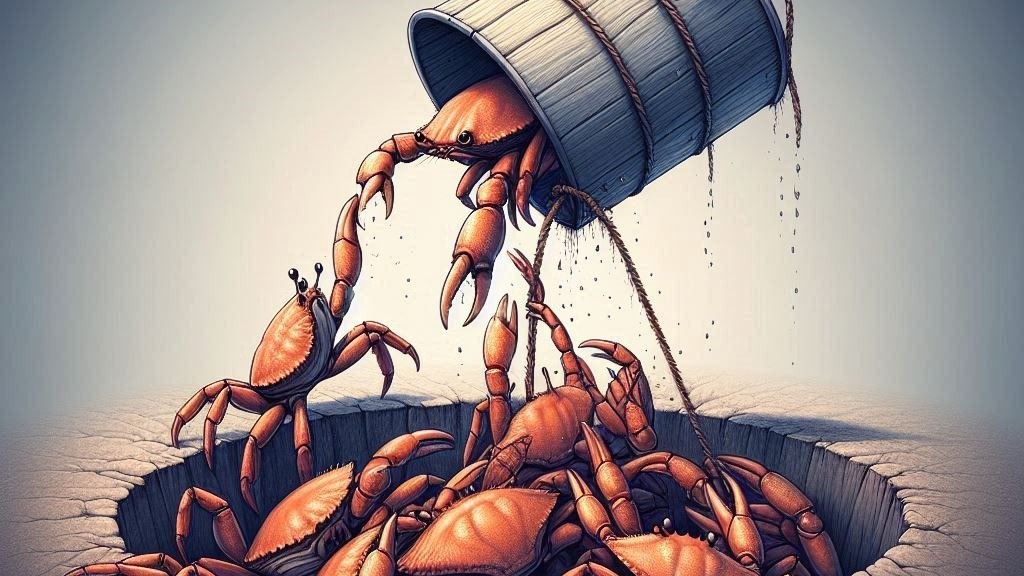

Crab mentality refers to the situation one can explore by placing a crab or a collective of crabs in a bucket. A lone crab can inevitably crawl out of the bucket, however, a peculiar scenario would arise if one situates a group of crabs in a bucket. As a crab tries to crawl out, the other crabs will pull it back down. If it tries again, the others will rip its claws off to ensure it can never do so again. Ultimately, no crabs can go anywhere besides the stew pot you are brewing.

Crab in a bucket scenario (Image source: Microsoft Designer)

It is naivety to assume human beings are a unified collective group. History, wars, and jealous conflicts are testaments to human being’s selfishness. Hence, it is arguable that we are inclined to place ourselves above others, even if it means at the expense of our peers. Despite being a precarious thought, this insight opens new dimensions to understanding crab mentality in the human context.

“Remember your cousin Timmy in China? He has 15 years of experience. He’s nine!”

Steven He’s dad (played by Steven He) exclaimed.

Terms like “Asian-level difficulty,” “Tiger Moms,” and “Asian parents” have become widely recognized through memes, movies, and other mainstream media, serving as a lens for global audiences to understand and appreciate aspects of Asian culture. Yet, one community still paints a negative view of the Asian community, even discriminating against its individuals – and the answer is ironically the Asian community itself.

The purpose of this work is not to discriminate or criticize any peculiar group but to foster intellectual discourse and encourage reflection on societal dynamics and individual perspectives. The chosen quote embodies this intention, capturing four intertwined facets.

Understanding the concept of face is crucial when discussing Asian culture and heritage. Face serves as a societal construct that governs social interactions and determines one’s standing within a social hierarchy. It is a dynamic measure that can be given, earned, taken away, or lost, often extending beyond the individual to include family and friends. For those unfamiliar with this concept, here’s a simplified explanation:

- A wife who earns a promotion gains face for herself in front of her boss, while also bringing face to her husband and parents through her achievement.

- Conversely, a student who performs poorly on an exam loses face among peers, and their parents, in turn, lose face within their social and familial circles.

Despite being debatable, visualizing face as a form of currency provides an interesting lens through which to examine crab mentality in Asian communities. Much like any valuable asset, currency must be earned, safeguarded, and strategically utilized. Losses, even those meant for long-term gains, are approached with caution and calculation. Consequently, individuals strive to enhance their reputation while using criticism to diminish the face of others.

The concept of face is deeply tied to education and parenting, playing a role in fostering crab mentality. Asian children are often raised to prioritize self-achievement above personal aspirations, adhering to predetermined paths for the “greater good” of the family. This emphasis on collective reputation often comes at the cost of individual dreams, reinforcing a mindset where personal success is weighed against familial expectations.

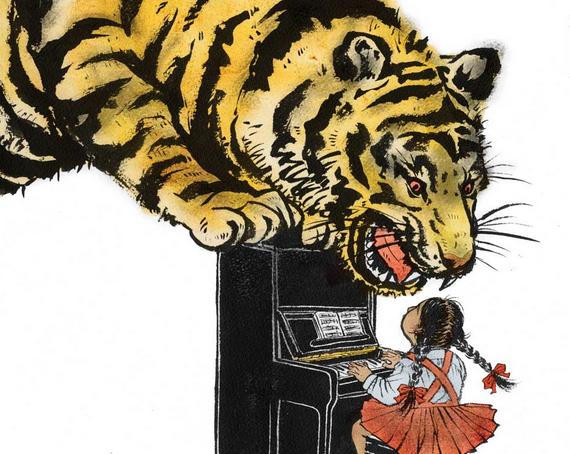

Parenting can affect mindsets, a reflection on Tiger Moms (Image source: Mims On The Move)

Indeed this is a generalized claim that leaves certain minorities for speculation, but the interplay between face and sacrifice is crucial in understanding the environment Asian children grow up. Literary works like Truyện Kiều (Tales of Kieu), a renowned Vietnamese poem, highlight traditional ideals through terms like cầm-kỳ-thi-họa—the four virtues defining a successful woman. Similarly, the stereotype of Asian children being expected to become doctors or lawyers has become a familiar cultural reference in contemporary discourse.

No parents want their children to grow up as bad people. Hence, it would be injudicious to blame parents and the system for a negative societal mentality. Yet, there are certain repercussions to sacrificing a child’s dream in return for a destined path to greatness. This leads to the third facet of crab mentality in Asian communities: A ramification for every child following the same success path means comparison and competition.

Let’s revisit Steven He’s joke: Timmy is used as a benchmark for comparison. The only way for Steven to save face is by climbing the same ladder and offering Timmy a similar spiteful insult. This vicious cycle of comparison fuels crab mentality within families, peers, and the broader community. True to reality, Asian students often spend countless hours in extra classes and clubs to meet rigorous expectations. Tiger moms push their children to excel in every class as if their lives depend on it. There is no middle ground—you’re either a winner or a failure.

This brings us to the final facet: the absence of praise and apologies. Ironically, according to BBC and Vocal Media, Asia is home to some of the politest people in the world, with countries like Japan and Thailand leading the way. Despite this, hierarchy plays a pivotal role in relationship dynamics. To save face, many Asian parents rarely offer praise to their children. Astonishingly, when it comes to apologies, parents often go to great lengths to defend their actions rather than acknowledge their mistakes.

A similar response can be seen in Asian workplaces, where higher-ups are more inclined to criticize and are far out of reach from their team members. Individuals will praise their peers and colleagues in hopes of receiving similar treatment instead of actual commemoration. Workers often segregate themselves into teams of interest to promote one another instead of collaborating as a group. These groups create outcasts who, despite their talents, are looked down upon and have their accomplishments taken or snuffed out by negative criticisms. This reluctance to give praise and apologize reinforces a mindset of self-achievement above all else. At first glance, mentality such as these are not wrong, but they leave cracks for detrimental thoughts of arrogance and selfishness – ultimately sustaining the crab mentality.

While this article explores the crab mentality within the Asian community, it is important to recognize that this negative mindset is not exclusive to any one group—it exists everywhere. The concepts of face, self-achievement, competitiveness, community, and sacrifice are what make Asian heritage unique and beautiful. This work argues that these cultural elements are not the root cause of the crab mentality, but rather, insights into why such a mindset may emerge.